From “Paper Life.”

The ruling center of Kievan Rus, the largest political entity in medieval Europe, and the early stronghold of Eastern Slavic Christianity, Kiev has long held a special place in Ukrainian and Russian history. Destroyed by the Mongols in 1240, and sacked again in 1416 and 1482, Kiev fell under Lithuanian, Polish, and ultimately Muscovite Russian rule.[1]

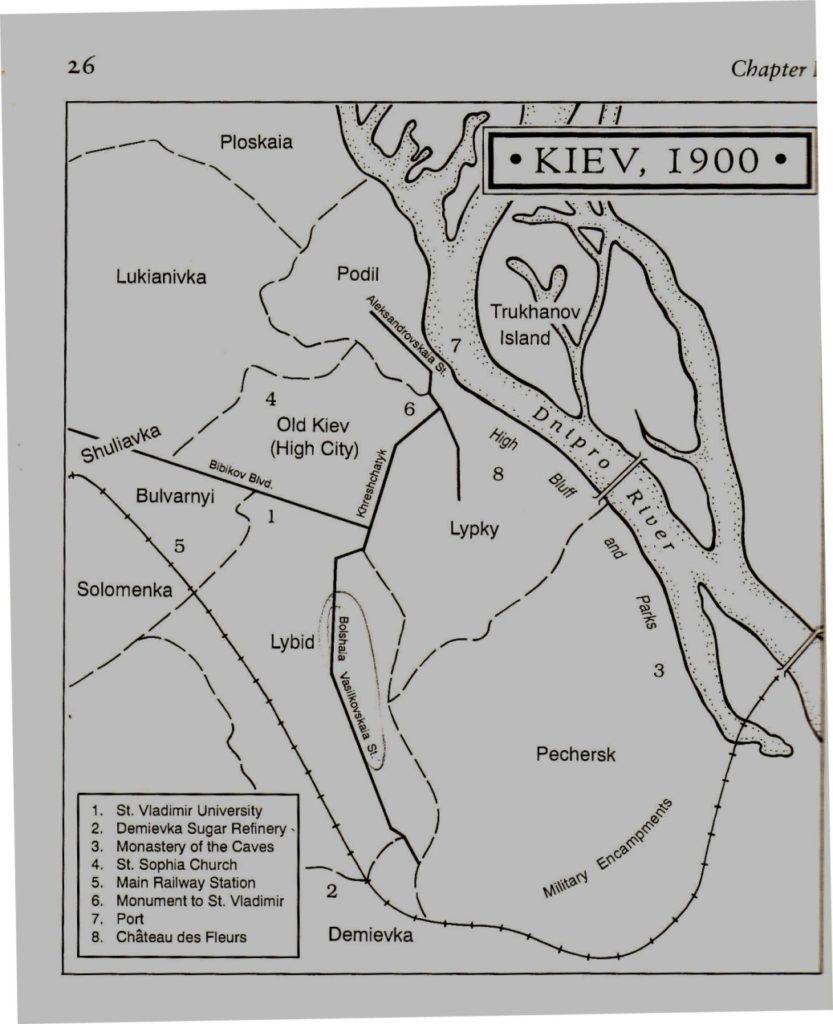

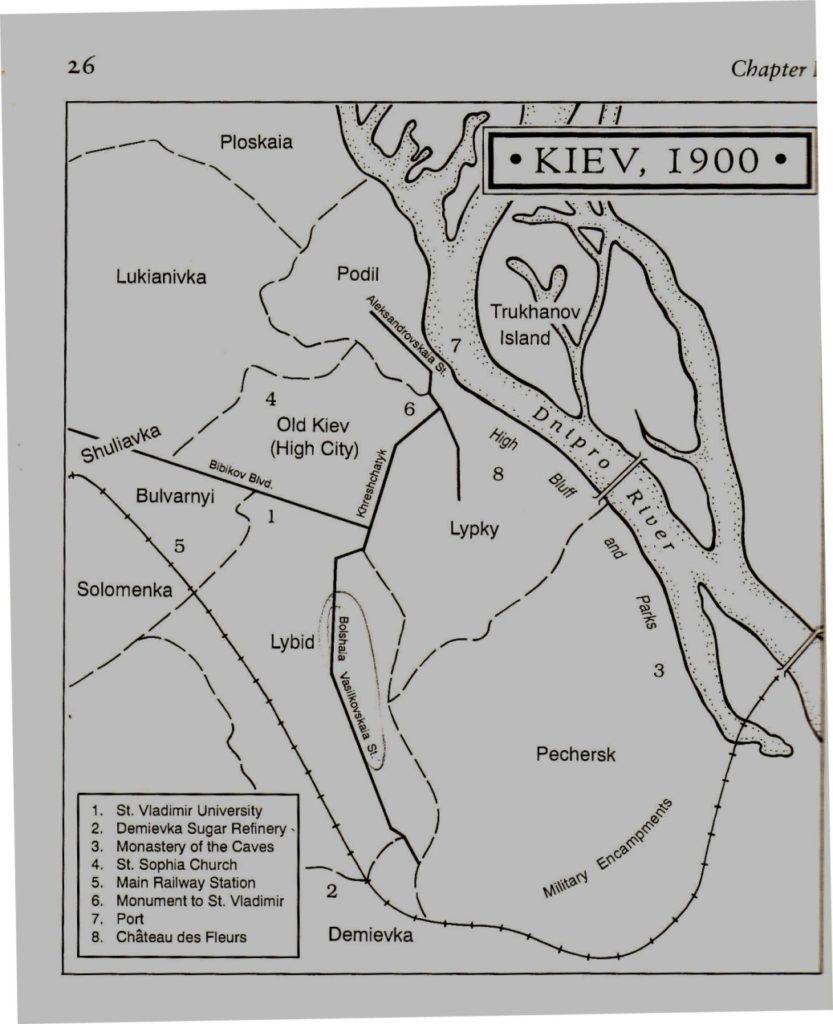

In the fifteenth century, Kiev came under the rule of the Grand Principality of Lithuania. They granted the Magdeburg Rights to Kiev, “…which enabled Podil’s (a neighborhood of Kiev) burghers to govern themselves as a semi-autonomous jurisdiction.”[3] This included tax exemptions and an elected magistracy, which over time came to constitute a hereditary “aristocracy.” These rights were reaffirmed several times over the centuries until they were entirely abrogated by Czar Nicholas I.

There are records of Jewish communities in Kiev from 1018 and from the 16th Century. Kiev’s modern Jewish community started in the 1790’s but was expelled in 1827. The Kiev Guberniya (province) was part of the Pale of Settlement, but the city itself was nominally off-limits to Jews. Nevertheless, merchants coming to the fairs had permission to reside there for the duration. From 1860 on, especially during the relatively liberal reign of Alexander II (1855-81), the Jewish community grew considerably, despite see-sawing decrees allowing and prohibiting residence. They included tailors like Meir Ronen, merchants, clerks, small business people, haulers, teachers, religious officials, boot-makers, carpenters, wood-turners.

Kiev was a stew of Poles, Ukrainians (whose language and culture was suppressed), Jews, many of whom came in order to trade in the great Contract Fair (1797) and a minority of Russians. Till the mid-19th Century, Poles remained highly influential, especially in education. Jews’ long association with Polish landlords served them well economically, but ultimately contributed to Ukrainian and Russian hostility.

A mere ten years or so before the 1893-95 births of our grandparents there was a major pogrom, leaving thousands of Jews homeless. Over the next several years many were expelled from Kiev. Yet, by 1897 the Jewish population surpassed 32,000 and included the Ronen family. By 1917, that number had reached 87,000+.[4]

One notable Jewish family was the Brodsky’s, who had come to Kiev from Brody in Austrian Galicia at the beginning of the 19th century. The Brodsky family developed a network of sugar refineries that eventually controlled a quarter of the sugar production in the Russian Empire. The family became major benefactors, establishing the Bacteriological Institute (a tuberculosis sanatorium), additional public health facilities including hospitals, and a trade school for Jewish boys, among many other philanthropic endeavors.The Ronen Family in Kiev Most of the letters Lev/Louis sent to Fenya/Fannie were to this address:

Vasil’kovskaya House # 31 [B stands for Bol’shaya = “Big” or “Main”]

Apt. # 36 To the 2nd Ronin

For Fenya Ronin

(What does “…to the 2nd Ronin…” mean? Were there two related families with that last name in the same building or apartment? Why would you need those words when the recipient’s name is right there? Was this some convention of addresses in those days? The answer remains unknown.

At some point the Ronen family moved to House 31, Apartment 24. By March, 1912 they had moved to Building 18, Apartment 4.[5]

Bolshaya Vasilkovskaya was and still is a major street in Kiev, known today as Red Army Street (Krasnoarmeiskaya). The Kreshchatyk was the main commercial district, built along a wooded ravine. It contained banks, the Stock Exchange and insurance companies. It is still an active location. At least one of the letters addressed to Fenya by Louis references the Kreshchatyk post office:

Dist[rict] Cap[ital] Kiev(Kreshchatik Post Office)To be kept until claimed.

To Fenya Ronin

There are many references to parks and the theater in the letters:

Nechama to Fannie

I go to the theater, go out, and am busy all day on weekdays…I saw Anyuta last week in the theater. I saw Goncharov’s “The Ravine.” Ach, if you knew what a marvelous piece that is. You, it seems read it and liked it a lot.[6]

This year many wonderful plays were staged. The repertoire in the People’s Theater is wonderful. I recently saw “Guilty without Guilt” and “Trilby,” two good plays; you’ve seen them and told me about them at home. [7]

Lev to Fenya

For Christmas the Ukrainian art lovers’ circle is planning a performance in the club. So, in all, it’s not dull. I’m very glad to hear that you often make it to the theatre.[8]

My dear, do you remember the evening when we were walking in the park and talking about our life? [9]

Ronen family to Fannie

We now often walk in Shato [park/garden]. Rosenfeld gives us tickets. This year it is so interesting there. They show movies, and you can see different concerts on the stage…

A new exhibition opened in Kiev. My girlfriend has some tickets and promised to take me. As soon as I see it I will write you the details.[10]

Between historical upheavals, work and financial worries, they still managed to enjoy life and what the city of Kiev had to offer.

However, life in Kiev deteriorated with the revolutionary foment of 1905, when a hundred Jews were killed in a pogrom over a couple of days, one of many that took place in the Kiev guberniya. The advent of World War I, the Russian Revolution and the subsequent brutal civil war brought increased suffering. As discussed in the “Historical Background” section, the assassination of Prime Minister Stolypin in 1911 impacted Kiev Jews directly, as did the Beilis trial. After Fenya emigrated from Russia in 1913 and World War I began, conditions worsened.

The last letter we have from the Ronen family arrived in 1922 after three years without mail.[11] The consolidation of the Soviet regime and the end of wars brought a semblance of stability, but we know that the suffering continued through purges and famines. Ethel Battalen Goldstein related her memory of Fannie crying during World War II because the letters from Kiev had stopped.

Footnotes

[1] Kiev, A Portrait, 1800-1917, by Michael F. Hamm, p. xi.

[3]Ibid p. 6

[4] “Jewish Kiev” from Kiev, a Portrait, 1800-1917, by Michael F. Hamm

[5] Chana Ronen, Kiev, To Fannie, March 12, 1915 or later

[6] Nechama Ronen to Fannie, Kiev, December 29, 1913

[7] Nechama Ronen to Fannie, Kiev, March, 1914

[8] Lev to Fenya, Voronezh, Let’s Go Abroad

[9] Lev to Fenya, Voronezh, December 23, 1910

[10] Ronen Family, Kiev, after April 15, 1913

[11] Franka Ronen to Fannie, Kiev August 30, 1922

|