The gates of memory opened for Pnina Goldsztern Shaufer (Perla) when I first spoke with her in October 2019, flooding her with memories and details of her young life in Poland. Based on conversations with her and her brother Shraga (Fayvel), I have pieced together this story of their family’s life in Poland before World War II, during the war years, and after the war.When writing of past events, I use their original Yiddish names; when writing about events after they arrived in Israel and in the present, I use their current names.

Pre-War

Before the German Army invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, the extended Goldsztern family lived a good life in Terespol and Brest, the small eastern Polish town and the big city situated across the Bug River from each other, which have been closely intertwined for centuries. It appears that though many of them had been born in Terespol, most of the family actually lived in Brest at that time, while some were still in Terespol. Among those living in Terespol was the family of Yaakov Goldsztern, Pnina and Shraga’s family.

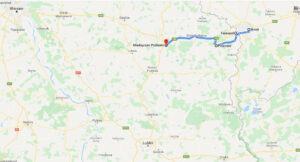

This map shows the locations of our family towns:

- Międzyrzec Podlaski, where the Rozenzumen’s lived.

- Piszczac, where the Goldshtern’s lived until about 1878.

- Terespol, where Berl Fayvel & Yocheved Goldshtern’s last six children were born and where the family of Yankel and Chaya Goldshtern lived.

- Brest, aka Brest Litovsk/Brisk, the “big city.”

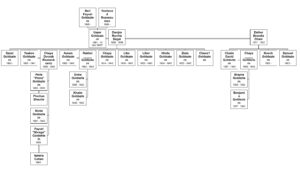

Their family consisted of Uszer Goldsztern, his wife Dvoira Segal and their children Szoel, Yaakov (aka Yankel), Avram, Chaya, Libe, Liber, Hinda, Zlateh and (probably) Chava. They were all born between 1903 and 1925 and were adults or teens by 1939. Dvoirah Segal Goldsztern died two months before the war began. Though the Yad Vashem Page of Testimony that Pnina filled out for Uszer seems to indicate that he owned a tallit factory, it was his father Berl Fayvel who did. My grandfather Sol described Uszer and his family as being religious.

Uszer had had three children with his first, deceased wife, Esther Brandla Cham: Chaim David and twins Noech and Shmuel. Other than their birth registrations, I have found subsequent documentation only for the eldest, Chaim David. Pnina had never heard that Uszer had been married before and it isn’t clear whether she knew Chaim David (aka David).

Uszer’s son Yankel married Chaya Blumenkrantz; Perla was born in 1935 and Rivkele, probably in 1937. He ran a general store in Terespol, where he sold food, fuel, sardines, “everything.”

Pnina described a lively extended family life, with the adult siblings and their families getting together frequently. She remembers that they put on plays together, including one about the biblical Joseph, in which her father played the lead. She remembered Uszer’s older sister, her great-aunt Tyla Freda Brandt, and related that the Brandt’s had a flour mill in Terespol, from which they sold flour wholesale. Tyla also had a son named Yankel, so the family distinguished between the two cousins with Yankel Brandt being “Tall Yankel” and Yankel Goldsztern being “Short Yankel.” She added that it was all relative, as no one was very tall. She remembered that the Brandt’s were “rich” and that Tila always had her Shabbat preparations finished by noon on Fridays.

Pnina also described visits from Yocheved, and it took me a while to realize that she was referring to Yocheved Rozenzumen Goldsztern, my great-grandmother. Yocheved was born in 1849 and by the late 1930’s she would have been quite elderly. Nevertheless, Pnina describes her as being alert and sharp, remembering all the many grandchildren’s and great-grandchildren’s names, and always bringing each one a unique kind of fruit. This little remembrance brought Yocheved to life to me as a real person, as something more than a collection of names, dates, and documents.

During the War

The early events of World War II set the context in which our family had to make life-and-death decisions; therefore, they are worth understanding.

Terespol and Brest were both part of the Second Polish Republic, established after the demise of the Russian Empire during World War I. As it became clear that war was likely, the USSR and Germany signed the Ribbentrop-Molotov Non-Aggression Pact on August 23, 1939. This agreement would divide Poland between the Soviet Union and Germany in the event of a war, placing Brest under Soviet control and Terespol under German control.

When the Germans attacked Poland ten days later on September 1, 1939, Perla’s mother Chaya was about to give birth to her third child. There was no one around to deliver the child because their country was being over-run by the Germans, so her husband Yankel roamed far and wide till he finally found a doctor willing to return to Terespol with him to help Chaya. Fayvel was born on September 4, 1939 and named after his great-grandfather, Berl Fayvel.

When Fayvel was a two-week old newborn and with their part of Poland over-run by the Wehrmacht, the family fled across the Bug River to Brest, where a number of other family members lived, including Uszer and Dvoira Goldsztern. Yankel and Chaya tried to convince the rest of family to join them in their flight further into the interior of the Soviet Union. However, at the time Brest was occupied by the Soviet Union and they assumed that the non-aggression pact protected them from the German army. Only Yankel’s 18-year old brother, Liber, joined them. About a month later, however, Liber grew homesick and returned to Brest. Bad decision.

The Nazis broke the non-aggression pact when they launched “Operation Barbarossa” on June 2, 1941 and invaded the Soviet Union; Brest was one of the first places to be occupied. The regular army was followed swiftly by the Einsaztgruppen, the “mobile killing units” which were responsible for the deaths of a third of the six million Jews killed in the war in what is now called the “Holocaust by Bullets.”

In November of that year the Nazis registered all the Jews of Brest and the surrounding area, and the ghetto was established that December. The following October 15 the ghetto was liquidated, and the remaining 50,000 Jews were shot in a mass grave at Bronaya Gora. Numerous members of our Goldsztern family died this way.

Pnina told me that her family found refuge in the “Tshenakovsky” region near Stalingrad for a period of time, and that at some point they sat for a week on a boat docked on the Dnieper River. However, the order of these things it isn’t clear to me and I can’t locate the Tshenakovsky region; perhaps I misheard the word (Stalingrad, today Volgograd, is near the Kazakhstan border). In any event, the ship they were on was packed with refugees fleeing the Germans. As they sailed, they made stops along the way and at one of them, Soviet authorities boarded and announced that any man subject to the draft had to leave with them, immediately. Although he was a Polish citizen and not subject to the Soviet draft, her 36-year-old father Yankel was compelled to leave. He was never seen nor heard from again and is presumed to have died during the war.

After Yankel’s disappearance Perla, her brother Fayvel, sister Rivkele and their mother Chaya travelled by train with other evacuees further into the interior of the Soviet Union. The train stopped along the way so people could get off to gather food and water. It was Chaya’s habit to take the children off the train while doing this, so that if she missed getting back on the train, she would not lose them. At one such stop, while she was getting provisions, the train came under attack. Chaya ran back to the train, terrified at what she might find. She saw her three small children lying on the ground, the toddler Fayvel between his two sisters, and all were awash in blood. I can only imagine that Chaya must have been frantic and panicked at the sight. It soon became clear that all the blood came from four-year-old Rivkele and that Perla and Fayvel were safe. Perhaps Chaya had to bury her daughter right there and leave the tiny, unmarked grave behind, knowing it was the last she’d see of her little girl in this world. Perhaps she wasn’t even afforded the luxury of burying Rivkele. It must have been an unimaginably crushing burden, yet she had to carry on for the sake of her two remaining children. That is what she did.

Chaya, Perla and Fayvel ended up in Dzambul, Kazakhstan with other evacuees and thus survived the war. While there, Chaya got sick, went to the hospital, and took little Fayvel with her, but she couldn’t also take Perla, so she was sent to a children’s house, essentially an orphanage. Perla did not know where her mother was, and Chaya had no idea where Perla was or how she was living. This was just one of the terrible traumas and periods of endless uncertainty that they suffered during the war.

Their ability to stay together as a family was not assured: Chaya’s doctor told her that she was very ill and likely to die and he offered to take Fayvel and raise him. Chaya gathered whatever energy she had left and insisted she would never let Fayvel go as long as she had breath left in her body.

In another close call, and unbeknownst to Chaya, the orphanage was sending healthy-looking kids back to Ukraine, probably to reduce the number of children for whom they were responsible; why else would you send children back to an active war zone?? Perla, who was probably about seven or eight then, was too underweight to be considered healthy and thus escaped being sent thousands of miles west where the war still raged. When Chaya finally got out of the hospital, she didn’t know where Perla was, and Perla had no idea where to find her mother. At this time, a neighbor of Chaya’s who had been starving and had taken some beets to eat, was sent to jail for theft. Before she was imprisoned, she placed her son in the same orphanage and recognized Perla there. This woman told Chaya where she had seen the child and the two were finally reunited.

After the War

From sometime in 1946 until March 1949 when it closed, Chaya, Perla and Fayvel were at the Displaced Persons’ Camp in Wetzlar, near Frankfurt and in the American-occupied zone (Yad Vashem article; US Holocaust Memorial Museum article). There were a number of different schools operating there and Perla and Fayvel attended the “Tarbut” school, which had a secular curriculum focusing on science, Hebrew studies (language and history) and the humanities.

Pnina remembers vividly that they got letters from an uncle in the US; she thought they were from Grandpa Sol but Grandpa never mentioned this family to me, even when I asked him directly what he knew about any survivors in his family. I thought the letters might have been from his brothers Meier or Shimon but in our second conversation, Pnina’s daughter Tova said that all her life she’d heard about the letters from her uncle “Sol Goldstein” in the US.

In 1948, Sol Goldstein wrote to Chaya that he could get them visas to come to the US. Chaya wanted to go there, but the children insisted on going to the new state of Israel. Surely life would have been easier for Chaya in the US; Israel was a very poor country in the early days of statehood, with food-rationing and a severe housing shortage. When they arrived in Israel, Perla became Pnina and when he started high school, Fayvel became Shraga; his last name became “Goldshtein” due to a clerical error that went uncorrected.

When the Goldsztern’s left Germany for Israel in 1949 the letters from Sol ceased, and they never knew why. But I recently heard from my cousin Sharon Kimelstein, whose grandmother Mary was Sol’s second wife. Sharon wrote that “Sol did have family that they wrote to. But after a while, and I don’t know the time frame, the letters came back marked ‘address unknown.’ Our Grandparents never mentioned Israel or that survivors were there. Perhaps they did not know and without our modern search engines, families disappeared, and bonds dissolved.” Now we know how the connection was severed. I am dismayed that when I asked Sol who had survived the war, he did not mention this family; I would have been able to find them much sooner, as much as 30 years ago.

Chaya was 41 years old in 1949 when they went to Israel; she never remarried and died in 1986. She worked as a cook in a school and was on her feet all day; as she had suffered frostbite while in Kazakhstan, this must have been painful, but her children said she never complained. She contacted “the Kremlin” in an attempt to learn her husband’s fate. Despite Yankel having been “drafted,” she was told that Yaakov Goldsztern wasn’t on any lists at all, not as soldier, not MIA, not a POW, not hospitalized, not killed, not deceased. Nothing.

As if all of this wasn’t enough heartbreak, years later Chaya came close to having to endure even more. Shraga, who had served in the Israel Defense Forces in the Engineering Corps, was called up for reserve duty early in the 1973 Yom Kippur War and was stationed about 15 km away from his home near Haifa. For several days, the reservists just sat there and were not ordered into action. The commanding officer sent one of them on leave with instructions to contact all the soldiers’ families and to report that their husbands and fathers were just sitting there, they were okay and hadn’t started fighting. Shraga’s four-year-old daughter Ronit answered the phone and what she heard was, “Father is in captivity and everything is okay” (in Hebrew the words “sitting” and “captivity” have the same root). When his wife Natalya, sister Pnina and mother Chaya heard this, they of course became hysterical, believing that Shraga was a prisoner of the Syrian Army. Desperate for information, they began making frantic phone calls. Three days later, the military powers-that-be reached Shraga’s commander, who told him that his family was going crazy and he should go home at once to reassure them that he was alive and free. Today it’s a cute story but at the time, the terror and dread must have been overwhelming.

Chaya lived through five wars: World War I, World War II, the Sinai Campaign in 1956, the Six Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973. In addition to her husband and daughter, she lost her immediate family and who knows how many other relatives. The price of survival was very high.

Can you clarify something? You say Yocheved is our great grandmother. Was she Molly’s mother? Did I miss something, or did you mistake the generational difference? Thanks for clarifying.

Just saw this.

Yocheved was Sol’s mother; all the Goldshtern/Goldsztern information is for Sol’s family. Mollie’s mother was Anna Goldberg/ Goldenberg Chalowskaya. I have very little information on Mollie’s family in Russia, just her parents’ names and probably location where she lived (Krivoye Ozero near Kamenets-Podolsk, now in Ukraine). I know that Harry and Ida were half-siblings whose mother’s name was Sara Chalowskaya (I know this from Ida’s ship manifest). That is the extent of what I know and can confirm.

By the way: Chalowskaya=Chalofskaya=Chalofsky=Chalowskii=Chalowskiji. All the same name, just in feminine or masculine form. Spelling is irrelevant.

Most of the information I have on any of our grandparents’ families is for the Goldshtern’s, in large measure because Polish metrical records (birth, marriage, death) are extensive, very informative, very accessible and written in Latin characters rather than Cyrillic.